At the turn of the 20th Century, a debate was raging in astronomy about faint, fuzzy objects called "nebulae." Some astronomers thought nebulae were small clusters of stars in our own galaxy. Others saw some of them as giant, distant collections of stars, some larger than the Milky Way itself.

Finally, in 1924, American astronomer Edwin Hubble measured the distance to what was then called the Andromeda Nebula. He found it to lie over 2 million light-years from Earth. It was the first object to be recognized as another galaxy.

Hubble's discovery changed our view of the universe. The already vast distances between stars were dwarfed by the incredible distances between galaxies. The universe was suddenly a much larger place than anyone had ever imagined.

The Sloan Digital Sky Survey has found more than 130 million galaxies so far. In this project, you will look at some of them to learn about different types of galaxies.

People seem to have a built in need to sort things into bins. In science, this sorting step is often a first step in looking for the underlying physics that is causing morphological differences between systems. After he established the extragalactic nature of some types of the nebulae, Edwin Hubble tried to define ways to classify these new galaxies according to their appearance, or galactic morphology. Using a large set of images and the standard scientific approach in a new area of research, he tried to classify different objects by type and then to arrange them in a system that showed smooth transitions from one type to another. The act of classification does not lead directly to a physical theory, but the hope was that the relationship between galaxy types would have a physical underpinning. For example, the galaxy types might be related by age, by gas content, by stellar populations, by mass differences, or by rotational differences.

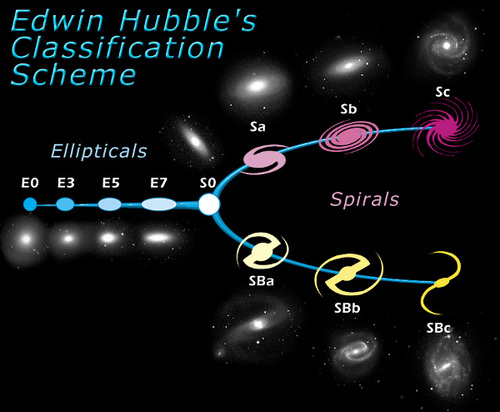

Hubble found three major types of galaxies in his study of the regions of space beyond the Milky Way: spiral, elliptical, and irregular galaxies. He also noted that many spiral galaxies also possess a central bar. Hubble classified the galaxies using a "tuning fork" system. The elliptical galaxies made up the fork's handle, and spiral galaxies and barred spiral galaxies make the fork's prongs. So his classification system looked like this:

|

| The Tuning Fork Diagram |

Hubble believed that galaxies started at the left end of the tuning fork when they were young, and moved toward the right as they aged. Therefore, he called elliptical galaxies "early galaxies" and spiral galaxies "late galaxies".

We now know he was mistaken in this belief. Spiral galaxies have a great deal of rotation and elliptical galaxies do not. There is no way an elliptical galaxy could spontaneously begin rotating, so elliptical galaxies cannot turn into spiral galaxies. Although Hubble was wrong about his theory of galaxy evolution, the confusing names have stuck: today, elliptical galaxies are still referred to as early galaxies and spirals as late galaxies.

Spiral galaxies are often considered the most beautiful of all galaxies. Ranging from flower petal shaped flocculent spirals to pinwheel shaped grand design spirals, these magnificent systems are found in low density regions of the universe where their fragile structure can escape the tortures of gravitational interactions with similar-massed sister systems. Spiral galaxies make up roughly 30% of all systems, and often host their own armada of significantly smaller satellite galaxies.

|

|

|

|

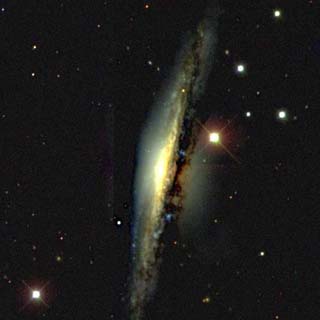

Three contrasting spiral galaxies:

a face-on spiral galaxy with tightly wound arms (left), a face-on spiral galaxy with very loose arms (center) and an edge-on spiral galaxy (right) |

||

Structurally, spiral galaxies consist of 1 or more (typically two or more) arms that spiral away from either a central nucleus or a central bar. These galaxies are sub-categorized based on the presence of a bar into S for Spiral and SB for Barred Spiral galaxies. These general bins are further broken up based on the the size of the galactic nucleus and how tightly wound the galaxy's arms may be. A galaxy with loosely wound arms and a small nucleus is a Sc galaxy. The label Sa is given to galaxies with a large nucleus and tightly wound arms.

Spiral arms typical possess gas and dust that feed ongoing star formation (although exceptions exist). Star formation is most prominent in the arms. All nearby spirals that have been searched for a supermassive black hole have shown evidence of a black hole that has a mass proportional to the size of galaxy's nucleus or spheroid of stars. By measuring galactic rotation curves it has also been shown that spiral galaxies are typical rich in dark matter.

While elliptical galaxies are often visually boring, they are also

the most common shape of galaxy found in the universe. These cotton

balls of stars range in shape from nearly perfect spheres to elongated

cigars.

In the Hubble galaxy classification scheme, elliptical galaxies are

denoted by the letter E. They are also given a number from 0 to 7. An E0

galaxy looks like a circle. An E7 galaxy is very long and thin, like a

cigar (with the caveat that a cigar-shaped galaxy viewed end on will

appear round with a small radius).

|

|

|

|

M89 - an E0 galaxy

Courtesy the Digitized Sky Survey |

M32 - An E2 galaxy

Courtesy AURA/NOAO/NSF |

NGC 4621 - an E5 galaxy

Courtesy the Digitized Sky Survey |

Elliptical galaxies have very little gas and dust. Since stars form from gas, little star formation occurs in elliptical galaxies. Most of their stars are old and red.

Elliptical galaxies have a large range of sizes. The largest elliptical galaxies can be over a million light-years in diameter. The smallest "dwarf elliptical" galaxies are less than one-tenth the size of the Milky Way!

Current estimates indicate that roughly 3% of all galaxies defy classification into one of the primary bins (elliptical or spiral). These systems vary in size from small systems that look rather like bright blue bug splatter on a wind shield, to large systems of unusual morphology. Classified by Edwin Hubble as Irregular galaxies (Irr), these systems have few unifying characteristics. The exact cause for all these different ill-defined shapes is poorly understood.

Other than having stars (and most likely a central supermassive black

hole), the only unifying characteristic of these systems is their ill

defined shape. Many, but not all, are undergoing star formation. Many,

but not all, show signs of a recent gravitational interactions with

another galaxy, or of a recent merger event. Most, but not all,

irregular systems are found in dense environments. Systematic studies of

all the different shapes, colors and environments of these systems are

ongoing, and making for a complex puzzle for computer simulations to try

and replicate.

back to Computer Lab 2: Exploring the Galaxy Zoo